By Courtney Leigh Church, Feb. 1, 2019

Ancient epic turned novella turned play, “Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad” recounts Homer’s Greek poem from the perspective of Odysseus’s wife, Penelope, on the Spriet Stage at London’s Grand Theatre.

The curtain rises on the ashen depths of Hades where the spectre of Penelope (Seana McKenna) is adrift in the afterlife. Addressing the audience directly, Penelope tells us the story of her life. She recounts her fraught relationship with her parents and her jealousy over her cousin Helen’s (Ellora Patnaik) acclaimed beauty. She shows how Odysseus (Praneet Akilla) wins her hand in marriage and tells us of the two sailing away to his home, Ithaca. Soon after the birth of their son, Telemachus (Tess Benger), Odysseus is summoned to Troy to fight for the Greeks in the Trojan war.

Abandoned by Odysseus and left to run a kingdom on her own, Penelope’s domestic epic beings.

“The Penelopiad” serves as a feminist re-telling of a deeply masculine story, but her version of events is more than just an echo of an epic. Penelope’s authority and wit are decidedly feminine; in her world power is derived from subtly undermining men who take her femininity for granted. Here, women are the cunning heroes upon whom Ithaca depends and weaving is the weapon of choice.

Penelope’s narrative challenges and parodies the original tale of Odysseus with feminine flair, but despite the authority Atwood affords her, our heroine is not immune to scrutiny. Penelope’s yarn is interrupted by and intertwined with the stories of her twelve former maids whose lack of voice, I’d argue, fuels the show.

The chapters in Atwood’s novella alternate perspectives between Penelope and the maids. On stage, however, the balance falls in Penelope’s favour. She appears to be our story’s sole weaver and the maids are merely caught in the threads of her tale. Yet their dissent remains clear as they haunt Penelope, chanting, “We had no voice, we had no name, we had no choice.” Shaken by overt on-stage sexual violence and harmed at Odysseus’s command, the maids are also the most emotionally moving characters on stage.

If “The Penelopiad” is about subverting dominant stories and making room for tales less often told, it also self-reflectively points to the stories we privilege and those we continually overlook.

This multi-layered performance is in excellent hands under director Megan Follows, a former Penelope herself, and a decorated cast of Stratford and Shaw Festival veterans.

McKenna’s Penelope is the perfect balance of maturity and energy. Visually, her white hair and grey dress cement her place in the underworld. At the same time, her youthful dynamism shines through the hellish grey lights of Hades. McKenna commands the stage and it is through her that the various threads of the play converge and disperse.

Akilla’s Odysseus is a brilliant satirical take on the hyper-masculine epic hero. Akilla is the first male actor to play Odysseus in “The Penelopiad”, a casting decision that initially seems too conservative for Atwood’s fierce critique. However, flexing his muscles and tossing about handsomely from scene to scene, Akilla is true to Homer’s character while simultaneously calling attention to the farcical side of Odysseus’s bravado. He and McKenna have tremendous chemistry in their shared scenes.

Monice Peter’s Eurycleia offers a seductive take on Odysseus’s nursemaid. She serves as liaison between Odysseus and the maids, but notably sidesteps Penelope in favour of the strapping prince. Peter and Akilla share an intense sexual chemistry in contrast to McKenna’s youthful inexperience.

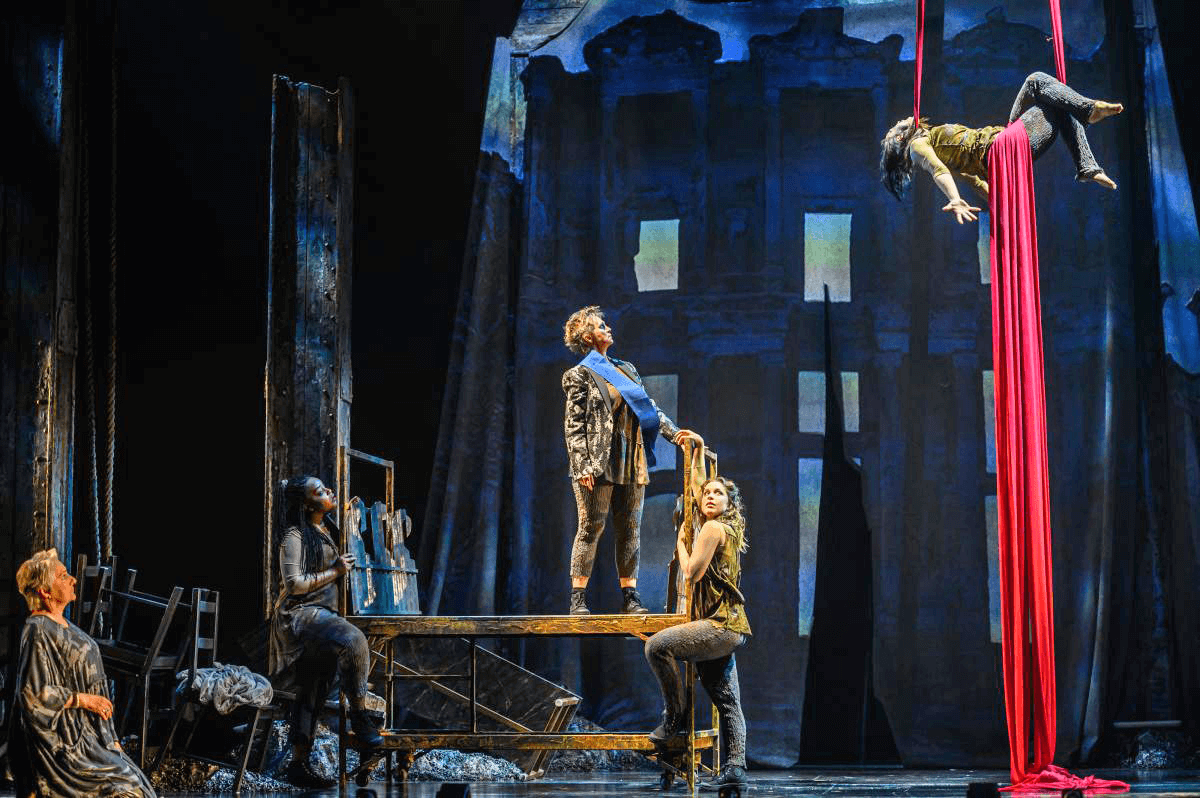

The Grand’s production has an extraordinary aesthetic. Charlotte Dean’s set design relies on a bleak backdrop of muted greys to situate the scene firmly in the bowels of hell from which Penelope spins her account. Against this backdrop, bright red props and aerial silks foreground the movements of the ensemble whose bodies, clad in dull tones, blend into the background. Bonnie Beecher’s lighting and Jamie Nesbitt’s projections don’t overwhelm the stage or negate the bleak backdrop but instead emphasise dynamic movement through the subtle play of light and dark.

Dana Osborne’s costume design is also noteworthy, especially Naiad Mother’s (Ingrid Blekys) bright blue gown which ebbs and flows with Blekys’s every move. Penelope’s wedding gown is also impressive. Foreshadowing the difficulties to come, the dress she wears throughout act one entangles Penelope as she fights to unwind herself from the authority of those around her. The dress is also used in several set pieces, cleverly connecting Penelope’s body to the space around her.

The Grand’s production of “The Penelopiad” breathes life into Atwood’s cleverly netted script. The result is a show that is entertaining and thought-provoking, both comical and, at times, deeply uncomfortable.

Details, Details:

“Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad”

The Grand Theatre

Jan. 22 – Feb. 9

Purchase Tickets Online

Box office: 519-672- 8800

Courtney Church is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of English and Writing Studies at Western University, where she researches modern and contemporary British theatre. Most of her time in the theatre is spent behind the scenes, tinkering with set design and thinking about props.

Courtney Church is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of English and Writing Studies at Western University, where she researches modern and contemporary British theatre. Most of her time in the theatre is spent behind the scenes, tinkering with set design and thinking about props.

What did you think?

You May Also Like

The Penelopiad: Listen to The Maids

Review: ‘A Christmas Carol’ at the Grand

Review: ‘Fences’ at the Grand

Margaret Atwood at Alice Munro Festival